Chernobyl- Of zombies and hope

05/24/2012

The following article, written by Glen Browder, Eminent Scholar in American Democracy at Jacksonville State University, originally appeared in the Sunday, May 20, 2012 edition of the Anniston Star.

In a few days, Hollywood premiers Chernobyl Diaries, a horror movie about six teenaged “extreme tourists” who visit the radioactive hotspot on vacation, only to discover that the place is populated by mutant zombies. Pre-release comments range from “Awesome!” and “I can’t wait” to “video poop” and “teen-flick nonsense.”

I was thinking about that upcoming zombie movie as I flew across the Atlantic Ocean to take a ground-zero look at Chernobyl to see how the people in that part of the world are handling their fate a quarter-century after the 1986 nuclear reactor explosion. There are no real zombies, of course, but the ghost of Chernobyl still haunts millions of people in that contaminated region.

According to recent research, contaminated chunks of eastern Europe are experiencing above-average cancer risks, and that is not all. Some, particularly young people, are developing psychological problems; they cannot find jobs, and they’re being excluded from broader society. The most cruel and disturbing development is the emerging rumor of “Chernobyl HIV,” a whispered warning against romance and friendship with impacted individuals.

On the ground at Chernobyl

I spent the last week of April in contaminated areas of the Ukraine, as part of a group of parliamentarians and journalists commemorating the April 26 anniversary of the reactor explosion. We also looked at the humanitarian efforts of Green Cross International.

Green Cross (founded and led by Mikhail Gorbachev) conducts varied programs designed to intervene at the family level and mitigate damage being wrought by the Chernobyl catastrophe. This organization supports community initiatives such as orphanages, therapy camps, mother-and-child clubs and micro-loans for family businesses.

I took part in this endeavor mainly as an unpaid senior advisor to Green Cross’ Environmental Security and Sustainability Program, but the group also invited me as the congressional representative of an environmental hotspot that, like Chernobyl, once posed a threat of man-made catastrophe with many potential victims.

For those too young to remember, our area discovered in the early 1990s that we were sitting on a monstrous stockpile of chemical weapons at Anniston Army Depot, enough nasty stuff to kill every man, woman and child in the country. Fortunately, after a gut-wrenching community debate, we proceeded to destroy every last bit of toxic poison, without a single fatality or serious incident at the incinerator.

While the situations in Alabama and Ukraine obviously were different, there was always the possibility of something going wrong here as it did there, endangering hundreds of thousands of innocent people.

So, as I surveyed the ravages of Chernobyl in eastern Europe, as I talked to people who lost loved ones in that horrible accident, as I talked to young people struggling with related illnesses, and as I talked with ordinary people still living in a radiation-contaminated environment, I constantly thought of our experience back home in Alabama.

What did we learn?

Our group learned that the contamination is still widespread and splotchy, impacting as many as 3.5 million people in Ukraine, 3.7 million in Belarus and 2.7 million in Russia. Radiation overall is decreasing, but many places are still too “hot” for residency, farming, or any semblance of normal life. Thyroid cancer has spiked, and investigators suspect that other illnesses might be connected to fallout.

Just as importantly, mental-health problems afflict the populations of contaminated areas. A recent study of related research and focus groups reports:

“The broad findings from these two sources are convergent and clear: 25 years after the Chernobyl disaster, the populations affected at the time, whether by being displaced or exposed to radiation, have sustained neuropsychological consequences and these consequences remain of public health and medical significance.” (“The Psychological and Welfare Consequences of the Chernobyl Disaster,” 2011.)

My conversations with folks in this region were troubling mixtures of optimism about the future and concern about medical and mental issues.

Hopes and fears

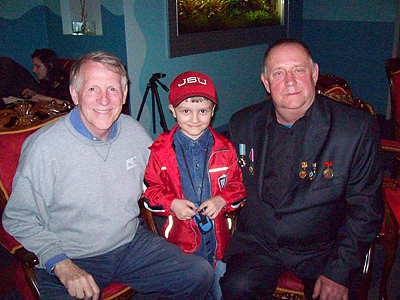

Zabirchenko Alexander is a 64-year-old Ukrainian who joined cleanup efforts in the days following the critical reactor explosion. “I later suffered serious symptoms, including heart problems, even though all my family was healthy and I had been in perfect health before then. I worry that my 7-year-old grandson, Kostia, will experience the same problems — he also has been sick.

Alexander has a right to be proud of his grandson, a bright, frisky, laughing kid to whom I gave my Jacksonville State baseball cap. But Dr. Jonathan Samet, a leading medical scholar from the University of Southern California and principal author of the previously cited study, told me that the venerable grandfather also has a right to be concerned. “I hope that we will find no biological or medical effects in the third generation, but I expect we will find serious psychological carryover.”

Sonny Patel, his research associate, added that “the most important thing that we can do is good research for planning; the worst we can do is give mixed messages to parents and children.”

These scholars will continue their work in the coming year; and they fear that this scourge will wreak major psychological damage among the new generation if not reined in soon.

Humanitarian Initiatives

Green Cross’ efforts are designed especially to help alleviate Chernobyl’s damage to families and young people. The group engages in medical treatment, provides mental-health assistance, supports childcare programs, trains families to grow and prepare safe food, and offers small financial-aid packages (like providing rabbits for commercial raising and marketing).

Larisa Kovalchuk, mayor in the contaminated village of Pakul, told me that the Chernobyl accident had more impact on her village than did the collapse of the Soviet Union. She hopes that the Green Cross-sponsored childcare center in her area will help mothers get out and earn a living for their families.

We visited the homes of some of her constituents. Larisa, a 39-year-old single mother of three, said that her sons Vladimir (18) and Dimytri (17) have weak immune systems and thyroid problems, and 2-year-old Victoria has already been hospitalized with similar ailments. Even though we spent only minutes in their home, it is clear they have a hard road ahead.

Another family, also living in the contaminated village, serves as a more hopeful example. They grow their own food and run a rabbit business that was financed by a micro-loan. Particularly interesting was Oksana, a shy, pretty 16-year-old who earlier experienced thyroid problems but has been doing better lately. She seemed like a typical teenager who said she likes to associate with her friends, enjoys school and wants to be a psychologist — “somewhere else.” Whether she realizes her dream depends on many factors outside her control. but I think she’ll make it.

The biggest threats

The humanitarians know their work is only a partial beginning and many things are beyond their reach, but they are passionate about their urgent mission. Maria Vitagliano, the Swiss director of Green Cross’ social and medical care program, bluntly talked about conditions eroding young lives in the region. “I think we will see all of the effects from the past, because up to 10 million people will continue to live in contaminated territory.

“But the biggest threats … are that their families and friends are burdening them with worries, that businesses are avoiding investments and jobs, and that society is stigmatizing them as victims rather than survivors. We have got to stop these practices and give young people a real chance for a better life.”

Prayers for eastern Europe and Alabama

Flying back toward Alabama, I thought about the similarities and differences between our experience and the continuing plight of millions of people in eastern Europe over the past quarter century.

The people over there have suffered aplenty with medical and mental problems — and nasty rumors. Now there’s added adversity due to economic exclusion and social shunning. Who knows what might have happened here if there had been a cataclysmic accident at the incinerator. Certainly, Hollywood would have loved to make movies about Alabama zombies, some in our own midst would have relished gossiping about Anniston HIV.

I said a prayer of thanks for our Alabama community. We had a hard time deciding how to deal with chemical monsters, but our fight is over and won. And I lifted a special prayer of hope for those unfortunate souls in far-away villages still haunted by nuclear hell. Many Ukrainians, Belarussians and Russians live lives tainted with medical, mental, economic and social risks. Absent success by intervening humanitarians, jobs growth and societal compassion, Chernobyl will continue to shadow the people of eastern Europe for decades.

Glen Browder represented Alabama’s 3rd District in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1989 to 1997. He now is the Eminent Scholar in American Democracy at Jacksonville State University.

More photos, courtesy of the author:

A teenager (Oksana Derkach) in the contaminated village of Pakul. Oksana seems to be doing better after early thyroid problems. She helps the family raise and sell rabbits, one of which she's holding. She wants to be a psychologist "somewhere else." She is referenced in the piece.

A mother (Larisa Yacoubet), daughter (Victoria), and local mayor (Larisa Kovalchuk) in the mother's home in town of Pakul in contaminated zone. Daughter, two-years-old, has had health problems; mayor is working to get a child-care center in the town. These people are referenced in the piece.

Orphans (unnamed) in an orphanage at Slavutych; the city was built from scratch in 1987 to house nuclear plant workers displaced from a "hot" city. It is in a contaminated area, but not as bad as other areas (all the soil was dug up and replaced with clean soil).

Browder and one of the "heroes" (Zabirchenko Alexander) who helped clean up the power plant after the explosion, with his seven-year-old grandson (Kostia), wearing a Jacksonville State University baseball cap. This is in Slavutych. Both are referenced in the piece.

A picture in the local museum at Slavutych showing what the Chernobyl nuclear power plant looked like right after the reactor explosion.